|

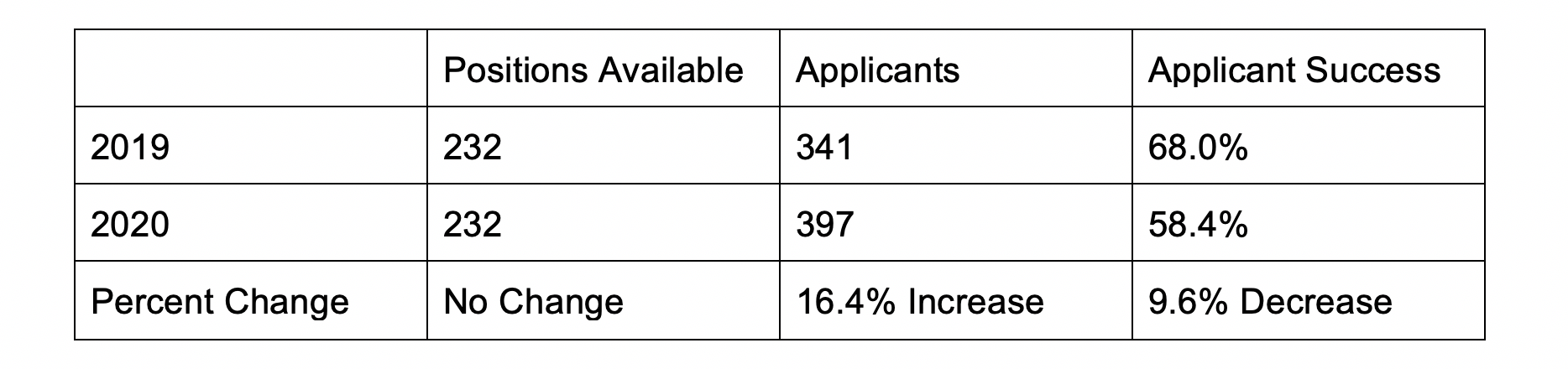

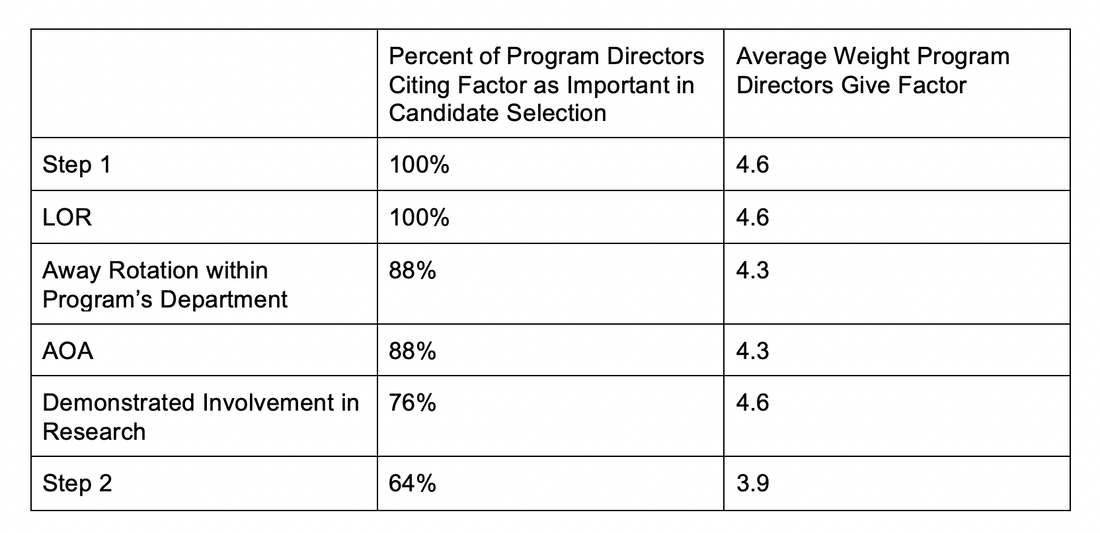

Not having a home program presents unique challenges in an already competitive process. This guide is intended for medical students wanting to pursue a neurosurgery residency without a home program at their medical school. Not having a home program presents unique challenges in an already competitive residency application process. To the authors’ knowledge, no comprehensive guide for medical students without a home program currently exists. The Basics Still Apply (They Just Matter More Now!) Neurosurgery continues to be one of the most competitive specialties for residency applicants. In the 2020 Match, there were 397 applicants for 232 positions, meaning only 58.4% of applicants were able to secure a residency position. The 2020 match saw an increase of 56 applicants with no increase in available PGY-1 residency spots compared to the 2019 match. This increase in applicants resulted in a nearly 10% decrease in applicant success. Clearly, neurosurgery has never been more popular to pursue nor more difficult to have a successful match. Perhaps this is partly why the most common advice you hear from program directors (PD) and mentors is “if there is anything else you could see yourself doing, do it instead.” Although neurosurgery is a truly unique field, some of the same general advice for application success still applies. Applicants will frequently hear that to succeed they need to ace the USMLE Step 1, get excellent letters of recommendation (LORs), and get involved in research. Although Step 1 is not everything in the residency match process, it carries considerable weight in candidate selection. The NBME’s recent decision to score the Step 1 exam as pass/fail will certainly have an impact on future resident selection. We include some information on prioritizing Step 1, which will be relevant for the next few years of applicants. This will not apply for the class of 2024 and later classes. In the last Charting Outcomes Report (2018), the average Step 1 score of US MD matched seniors was 245 (n=188). This was slightly down from the 249 average Step 1 Score reported in the 2016 Charting Outcomes. Step 1 scores ranged from less than 210 to greater than 260. Higher scores are correlated with greater success in the match, and higher than average scores are a way for students without a home program to distinguish themselves at top programs and improve their overall chance of matching. When surveyed, 100% of PDs (n=25) responded that Step 1 scores were an important factor in selecting candidates for interviews. Step 1 scores, along with LORs and research involvement, had the greatest average weight as factors in candidate selection. Step 1 is also a way that programs will screen for their rotators during fourth year, which makes it that much more important to do well as LORs from these away rotations also play a critical role in candidate selection. Applicant research activities are also considerably important to neurosurgery programs when selecting a residency candidate, reflecting the importance of research in the field of neurosurgery and the value placed on personality qualities fostered by commitment to scientific inquiry. Seventy-six percent of PDs cited “demonstrated involvement and interest in research” as a factor in candidate selection. Research endeavors demonstrate both interest and commitment to neurosurgery and its future. Additionally, since every applicant will be asked during interviews about their research experiences, discussing research is an excellent way to connect with faculty and residents while showcasing passion and knowledge. The Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) provides applicants a few ways to record their research activities. “Research experiences,” “peer reviewed journal articles/abstracts,” and “poster presentations” can be added to your application. Research experiences include any research projects you were involved in up to and including medical school. Peer reviewed journal articles/abstracts are limited to authorships published in the literature. Poster presentations include all presentations an applicant authored including those presented during medical school research day events. Neurosurgery applicants tend to invest considerable time into research activities. The average matched applicant in 2018 had more than five research experiences and 18 published journal articles, abstracts, or poster presentations. Cultivating a variety of research experiences during medical school is not only an expectation, but an opportunity to acquire unique experiences that can enrich personal statements and interviews. The third major factor that carries the most weight in applications is LORs. ERAS allows applicants to attach four LORs to their applications. LORs communicate valuable information to PDs about an applicant’s academic proficiency, research interest, professionalism, leadership, values, and character. Perhaps most importantly, LORs help interviewing faculty assess applicant’s interest in neurosurgery. As the longest and most demanding residency, programs need to be assured of an applicant’s commitment to the field, and glowing LORs increase confidence in an applicant. Considering this, it is generally recommended that all four LORs come from neurosurgeons, preferably PDs and department chairs. In neurosurgery, the expectation is excellence. In addition to stellar grades and board scores, robust research, and top-notch LORs, you need something unique about yourself to stand out, even if it is only to have something memorable to discuss during your interviews. This can include graduate degrees (MPH/MSc/MBA/JD), particular hobbies or interests (running, hiking, books, sports, music), and significant life experiences (challenges, losses, travel, volunteering). Don’t think too hard. Everyone has something that makes them different. It just may take some thought and practice on how best to showcase what sets an applicant apart. Circulating personal statements and practicing interviews with mentors, neurosurgery residents, faculty, friends, and student affairs staff can help applicants reflect on what makes them special. Now that we have covered the “basics” of what applicants need to have a successful match, let’s move on to the problem at hand - securing mentorship and research at medical schools that do not have neurosurgery departments. Mentorship Neurosurgery is a small, small field. There are less than 4,000 neurosurgeons in the United States, and fewer than half of them are in academics. Everyone knows everyone, especially in academia. Therefore, finding a mentor is absolutely critical. A good mentor will help you find research projects, advise you on where to apply for away rotations and residency, tell you how competitive you are (and how to make yourself more competitive), etc. Without a home program, it can be hard for a student to find a mentor. Local community neurosurgeons can indeed be helpful, but the connection to academic neurosurgery is higher-yield because of access to research and advising. In the pre-Covid-19 era, attending large national conferences provided a fantastic opportunity to network with neurosurgeons from around the world, and for the student without a home program, it was a valuable way to find a mentor. Registration fees, travel, and hotel rooms make conference attendance prohibitive, depending on the student’s medical school conference attendance policy, and not having research to present would compound this. Furthermore, with conferences being cancelled in the immediate future because of Covid-19, there is no telling when this opportunity will resume. Email and social media platforms have made connecting with other neurosurgeons easy and simple. We (the authors) have personal experience building connections over email and social media that have led to mentorship, away rotations, and research projects; indeed, the utility of these electronic forms of communication cannot, and should not, be overlooked. The AANS also has a service where students can connect with other research mentors, but in the experience of the authors, this service was less effective than direct messaging. Research One of the most challenging obstacles an applicant with no home program faces is finding research. As detailed earlier, a robust research portfolio is important for competitiveness in the neurosurgery match, and recent data demonstrate that the average number of publications continues to rise - especially for students from Top 40 medical schools. Students without a home program are at a disadvantage, making finding projects both critical and difficult to come by. In our experience, there are a handful of ways that an applicant without a home program can overcome the research barrier. One option that is widely used, even by students with strong home departments, is to take a research year. Many take their research years in between the second and third year of medical school, as this time marks the transition between preclinical coursework and clinical rotations and is easy for scheduling purposes. One may also decide to complete a research year between the third and fourth years of medical school, especially if an applicant had an experience in third year clinical rotations that inspired them to pursue neurosurgery, but this could prove challenging for scheduling purposes and the applicant may not want to interrupt the continuity of his or her clinical education. Another option is to defer matching for a year after graduating and conducting research then. Ultimately, it is up to the student when and where he or she decides to plan a research year based on his or her preferences and individual needs. There are numerous prestigious research fellowships offered and plenty of opportunities to get involved at centers conducting cutting-edge research (see a brief list below); the added benefit of this is to form relationships with these departments and investigators for future letters of recommendation, away rotations, and potentially matching. We advise applicants with less research output than published rates for matched students (especially those without a home program), those with Step 1 scores lower than average, and those who will be taking Step 1 P/F to strongly consider planning a research year. When seeking out research at neighboring or even faraway institutions, consider institutions with home programs and a strong track record in research. As mentioned earlier in this article, students should seek connections via mentors to find research, if this option is available to them. If not, email and social media platforms have made connecting with residents and attendings at academic centers worldwide breathtakingly simple, and the ability to conduct research remotely allows students without home programs to complete projects at other centers. An added benefit of conducting research at an institution with a home program is the opportunity to attend weekly academic conferences. This is an easy way to get to know the faculty and residents better, understand a program’s teaching curriculum, and explore the wide range of pathologies that neurosurgeons encounter daily. There is also the option of conducting non-neurosurgical research. While not the most ideal, there are benefits to this strategy. There are numerous fields that overlap with neurosurgery, including otolaryngology, radiology, oncology, trauma surgery, neurology, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, vascular surgery, and anesthesia. If there are opportunities for research in these fields at the student’s institution, projects can be designed that could generate “neurosurgically-relevant” research. Alternatively, the student could perform research outside of neurosurgery but in a field that they are still passionate about (anatomy, public health, socioeconomic determinants of health, health policy, organic chemistry, etc.), which demonstrates well-roundedness, intellectual curiosity, scientific inquiry, commitment, dedication, and the ability to see a project through to the end - valuable skills that can be applied to any field of research. Indeed, interesting projects outside of neurosurgery may offer the applicant the chance to distinguish themselves from others during interviews. Lastly, the student could elect to pursue another advanced scientific degree (such as a MS, MBS, or PhD), either during a gap year or after completing an MD/DO. These degrees would provide a structured environment and favorable access to research, though at the expense of time and extra loan burden. Irrespective of the type of research conducted and when, productivity is of the utmost importance. Publications are the “currency of the kingdom,” and research experiences that do not produce papers or abstracts will not benefit the applicant as much as having journal articles that can be listed on ERAS. When selecting a mentor or principal investigator, be sure to consider how productive he or she is and how likely you are to produce papers. Of note, the advent of a pass/fail Step 1 will likely increase the importance of research for matching into neurosurgery and could further disadvantage students who do not have a home program. There have been no formal recommendations issued by organized neurosurgical leadership as of yet, but the topic has been explored in other blog posts. The test being pass/fail may change the calculus of whether or not to take a research year or pursue another advanced degree for many students. Away Rotations Away rotations are the best way to show interest in a particular neurosurgical program, collect invaluable LORs, and to distinguish themselves through their work ethic and fit within the department. The best place to start when deciding on where to rotate is to reflect on what an applicant is seeking in a program. How important is geography? Is an applicant interested in an academic or purely clinical career? What subspecialty is the applicant interested in? What are the applicant’s research interests? Program websites can be useful to learn more about what a program’s strengths and weaknesses are. Do they have a strong functional or vascular department? Does their curriculum include protected research time? If an applicant has questions about a program, they can always reach out to program coordinators who can put them in contact with faculty or residents. Once an applicant can summarize what they are looking for and has a few programs in mind that fit that mold, they can ask their mentor if there are other programs they should consider. Together they can come up with a larger list. Lastly, the applicant should ask students who previously rotated at programs about their rotation experience. This can help students prioritize programs based on which ones are most likely to give them the best LORs. Applicants should try to complete as many away rotations at programs they are genuinely interested in as possible. This can be cost prohibitive and it can be helpful to consider programs in cities with friends/family members (who won’t mind you couch surfing). We recommend completing 3-4 away rotations if scheduling and finances allow, as you will need at least 3 LORs (preferably from neurosurgery chairmen or program directors) for ERAS. Keep in mind that the interview season usually begins in late October, so we recommend completing your away rotations by then. The key to success on an away rotation is to treat it like a job interview and to follow the residents’ lead. All residents have completed away rotations and know best what you are going through. They can offer you advice on what is expected. Pay attention and follow their advice. There is an instinct to overdo things when on an away rotation. It is very important to show your commitment. That includes reading up on OR cases beforehand, reading patient’s charts regularly, being prepared, and being present as much as possible. Simply being around and helping pre-round and staying to help past evening rounds gives programs the right impression. But DO NOT overstep. If you are asked to go find something out from a nurse taking care of a patient and the nurse is busy and tells you to come back later, do not be curt or demand their attention. Be respectful, be humble, and don’t be afraid of coming back empty handed. The worst thing that can happen on an away rotation is that you develop a reputation for being disrespectful or unprofessional. This could lead to a damaging LOR. As long as you show up, read up, and are genial, you will be successful. Covid-19 has turned away rotations upside down, and this will unfortunately severely impact students at schools without a neurosurgery department. The Society of Neurological Surgeons (SNS) has communicated that neurosurgery applicants without home programs should rotate at the program nearest them for 8 weeks. Applicants should coordinate this by emailing the program coordinators and explaining that they do not have a home program. They will understand your situation as it has been discussed by every program since March. If a particular program is unable to arrange a rotation, reach out to the next closest program and explain your situation again. Do not try to arrange a rotation at a distant site even if that program is of special interest to you. The SNS has released a letter saying they will look unfavorably on LORs from away rotations (unless you are an applicant without a home institution rotating at a nearby program). Applicants can still be successful on their away rotations by following the above advice (be prepared, be present, don’t overstep). Special Consideration: Matching as a DO student The 2020 match was the first year of the DO-MD residency merger. That is, DO students no longer applied to two separate matches. Instead, historical DO programs that earned ACGME accreditation were included in the allopathic match, while the remaining programs closed. This reduced the number of overall spots available specifically for DO students. Although this made matching more difficult, it ensured that all neurosurgical training programs meet the same standards and expectations as determined by the GME accreditation council. Matching into neurosurgery as a DO, particularly one without a home program, may seem impossible, but we can assure you it is not. In 2018, 10 osteopathic medical students applied into neurosurgery, and only 3 matched.1 These applicants, on average, had 7.3 research experiences, 21.3 abstracts, presentations and publications, and a 252 on Step 1. Although this is a small group, these averages surpass those noted of the allopathic applicants in the same year (5.2, 18.3, and 245, respectively). In the 2020 match, 18 osteopathic seniors applied and, again, only 3 matched. Our advice to you is the same whether you’re a DO or MD student. Conducting meaningful research in which you played an important role, finding a mentor who believes in your success, and networking at conferences or online are critical to your success in the match. It is helpful to reach out to programs to show your interest, and even more so if your mentor reaches out on your behalf to not only express interest, but also to vouch for your character, work ethic, and ability as a future neurosurgeon. It’s easy to feel like you’re at a disadvantage as an osteopathic student, but the key is to make yourself a competitive applicant and to network well - not only with mentors and residents, but also with previous DO applicants and programs with a current DO resident (rosters are typically available on the program website). Conclusion We are all in unprecedented times, and the landscape of applying into neurosurgery is changing frequently. As the applicant pool becomes more competitive, it’s important to seek all opportunities that will set you apart and ensure your success in the match. Whether this means taking a research year, pursuing another degree, or networking at meetings or virtually, we encourage you to give it your best effort. Not having a home program doesn’t mean you will fail, it will just take a bit more effort and determination to find the resources and connections you need. Neurosurgery is a small field, and we are all here to support each other! AuthorsJacob Kosarchuk, MD Brain & Spine Report is a product of the Brain and Spine Group, Inc. and the statements made in this publication are the authors’ and do not imply endorsement by any other group. The material on this site is for informational purposes only and is not medical advice. Unauthorized reproduction in prohibited. Categories All Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|

5/14/2020